Interpreters of Shakespeare's King Lear tend to fall into two camps. First are those who point to the play's numerous allusions to Bible verses and see it as telling a Judeo-Christian morality tale. The other camp is the nihilists, who find no transcendent values at all in the play; for them Lear's universe is one empty of divine beings. For them (e.g. Frye 1963, 1961) the Biblical references help convey how characters are seeing situations within the play, but point to no transcendent meaning apart from that character. The result is "a negation of the possibility of unity, coherence, and resolution" in the play (Felperin), a "radical instability" (Booth, both cited in Foakes 1997, 84f). Yet film versions, such as the Russian one or Lawrence Olivier's, do seem to have coherence and unity (Foakes 1997).

I want to try to reconcile these opposites. I believe that the Biblical allusions do express characters’ attitudes, but also point to a transcendent meaning--just one not within the traditional Christian framework, whether Catholic or Protestant. I wish to argue that the world-view of the play is something outside traditional Christianity, whether Catholic or Protestant, while also something like Christian salvation is attained by Lear at the end toward which the audience's alter ego, Edgar, bears favorable witness. It is not a salvation that requires belief in a historical Jesus and his historical sacrifice; that is part of the point of setting the play in pre-Christian Britain. It is more an expression of what was called the prisca theologia, the ancient theology that God taught Adam and which continued to be practiced in many parts of the world before Christ. It is a salvation through experience rather than through belief. In that sense it has affinities with certain strains of pagan philosophy. In the Renaissance there was Christian Neoplatonism, which connected with pagan Neoplatonism and its fascination with Orphic and Chaldean "Mysteries." Before the Renaissance, there were independent thinkers and poets during the Middle Ages, not to mention the heretics of those times. And before that there were figures such as Clement of Alexandria, Origen, and the independent subscribers to Christiantiy, but condemned by the orthodox, called Gnostics. There were also Jewish writers such as Philo of Alexandria and the author of the Wisdom of Solomon.

Among these various strands, I will be concerned with only a few: for one, a troubadour named Pere Cardenal,; for another, the ancient theologians of the type known as "Gnostic" by the heresiologist Irenaeus, whose work "Against Heresies" went through many editions in the century preceding Shakespeare. A third will be the alchemical texts of the time, which although Christian in orientation were based on previous works by Arabic writers. The content was something neither intrinsically Muslim nor Christian. I am not trying to argue that Shakespeare actually read these works. He probably was exposed to only a few of them. It is the point of view that matters, for clarifying the play. In that spirit, I will even be citing some works that he certainly could not have read.

Irenaeus's book on the "Gnostics so-called" went through numerous printings in the 16th century,

first as edited by Erasmus in 1526, later by others in 1570-1575

(Unger 1992). According to Irenaeus, only a few groups actually called

themselves “Gnostic,” but others were enough like them to group them

together. Even today Irenaeus’s survey defines the term “Gnosticism” as

used by modern scholarship

That it was Erasmus who published Irenaeus is of particular interest.

Scholars have noted the similarity in outlook between Erasmus’s own

work Praise of Folly and Shakespeare’s King Lear (Wood

2003). Speaking through personified Folly, Erasmus exposes the

foolishness in people’s apparent wisdom, in terms similar to the Fool

in Lear; at the same time he shows the wisdom in apparent foolishness,

in terms that bear comparison to the “mad” scenes in Lear. Actually

written in England, the book was immensely popular there, both in Latin

and in a 1569 English translation. I shall explore the similarities in

sections 1, 5, and 11 of this essay.

Erasmus, however, claimed to be an ordinary Christian believer;

and while his works were condemned after his death, that does not prove

that he was anything other than he claimed. For our purposes here, it

shows that the dividing line between heresy and orthodoxy is not always

clear.

Thanks to these various sources, the Gnostics were well enough known. A satirical travel fantasy written around 1600 and published in Latin

in 1605, with an English translation in 1609, manages to satirize most of the Gnostic sects mentioned by Irenaeus--and also by Augustine, in his On Heresy--in about three pages (Joseph Hall, Mundus Alter et Idem, pp. 103-105 of English version). Individual Gnostic

teachers were mentioned in mythology handbooks. John Donne preached a sermon against

Gnosticism in 1622. In part this upsurge in interest may have been that because of the victory

of Protestantism, Gnostic-like groups such as the so-called “Ranters”

were emerging spontaneously in England. (The name "ranter" was not necessarily a

term of abuse; besides meaning "harane", the term "rant" also meant “make merry.”)

So I will start with Irenaeus. Simplistically stated, what characterized Gnosticism for him was its positing that the god of Genesis is not the true god, even if he did create heaven and earth, but only an ignorant, arrogant, and foolish impostor.(See http://www.gnosis.org/library/advh1.htm, Book I chapter 5, sections 3-6; also chapter 26, section 1, and others). For some Gnostics, he was even evil (chapter 27, sect. 2); but very few of the teachers cited by Irenaeus say this--they say only that he did what was in fact evil through his ignorance and folly,. Above him stands a God of All, incomprehensible by humans, whom Christ came down to reveal, to those with ears to hear.

This critique of Judeo-Christian tradition implies a critique of a certain personality type as well, that represented by the god of Genesis. Such an insecure ego, given to rages and punishments when challenged, is found in abundance in rulers on earth. Christ’s message, for the Gnostics--one not unique to him, to be sure-- was that such a personality cuts itself and those following its lead off from a true relationship with the divine, which is a relationship to something beyond ego. It is such a relationship alone that makes for true peace of mind, independent of the vagaries of fortune and favor.

In this regard we are fortunate to have Jung’s 20th century psychological reading of the Gnostics. He has shown us how to read them in a way that describes the human. Where the Gnostics wrote disparagingly about the god of Genesis, Jung sees the shadow-side of the human ego. Where the Gnostics wrote of an Unknown God, Jung sees the Self, the inner totality of the personality, both conscious and unconscious, which communicates with the ego through our dreams, the unconscious goals of some of our actions, and our artistic responses.

Because of this psychologizing tendency, which King Lear participates in having its personalities conform to the personalities of Gnostic myth-making, it is possible to reframe the Gnsotic demiurge in less radical terms. We tend to think of God in terms familiar to us. In that sense, the Book of Genesis can be thought of as expressing a psychologically primitive conception of God, in which God is separated sometimes from His Wisdom; at such times, the shadow-side emerges. As humanity matures, its conception of God does the same. So instead of two gods, we may prefer to think of one God conceived in various ways, gradually integrating the power of God with his Wisdom..That perspective further blurs the distinction between Gnostics and thinkers who stay within the mainstream. However the distinction between demiurge and high god is nonetheless useful for psycholo9gical and exegetical purposes, between two major types of personality and conception of God. It is not the same as "Old Testament" vs. "New Testament," because the so-called "Old Testament" also contains both conceptions; the second type there is then, by Christian theologians, classified as "predictions" of the New Testament within Judaism..

As I have said, I will be drawing from two other traditions, both of which Shakespeare was likely familiar. One is that of the medieval troubadours, in what is now southern France. I will be citing just one poet, Peire Cardenal, who wrote in the 13th century and reputedly lived to almost 100 years of age, even longer than Lear’s 80. He lived long enough to see the unique culture of his beloved Languedoc destroyed by a half-century armed crusade by the Popes and the French monarchs against the Cathars, a Christian sect broadly supported by all classes of Languedoc society, but which the Church branded heretical. Many scholars (e.g. Hamilton 1999, 281; Quispel 2000a, 192f) think that the Cathars were the last Western European remnant of the ancient Gnostics. Cardenal's songs seem to suggest a sacred as well as secular meaning, and sacred in the manner of the Cathars rather of the Catholic orthodoxy he clearly despised. I do not know whether Shakespeare was familiar with Cardenal; again, it does not really matter.

The other tradition I will be using is that of alchemy, especially texts and pictures from the century or so before and the half-century after the appearance of the play. Here I build upon work begun by Nicholl (1980). We tend to think of alchemy as a medieval phenomenon, but actually its greatest flourishing was during Shakespeare’s lifetime, at the court of the Hapsburg Emperor Rudolph II in Prague, who employed dozens of alchemists. London had its own court alchemist, by the name of John Dee, and representatives of each center visited the other: Dee went to Prague in the 1580’s with his colleague Michael Kelly, and Rudolph’s physician Michael Maier visited London in 1612-1614 (Yates 1964).

In Shakespeare’s time, too, the works of earlier alchemists, notably Edward IV’s court alchemist George Ripley, were translated from Latin and printed with illustrations. After Shakespeare, alchemy continued to flourish in England for a century or more. Its devotees ranged from the mystic Thomas Vaughan (brother of poet Henry Vaughan) to the scientist Isaac Newton, who in his younger days is said to have spent more time on alchemy than he did on mathematics and physics. What is of interest here is less the chemical processes the alchemists described, which have been described better since, and more the spiritual meaning the alchemists projected onto their work, which comes out especially well in the illustrations that accompany their rather dense prose. Here Jung has provided important insights into how the alchemists’ quest may be understood in terms of psychological transformation.

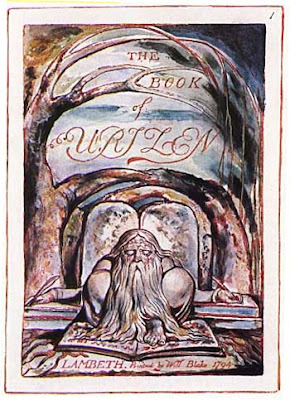

In very much the same spirit as alchemy are two famous artists, Hieronymous Bosch, from around the year 1500, and William Blake, around 1800. To help us get a sense of the feeling-states that go along with King Lear, I will illustrate Lear’s states and visions with examples from their works. Finally, I will use another visual aid to illustrate the play, namely, representations of the Fool in Shakespeare’s day, in popular art and in the decks of cards known as tarot, whose images were familiar in Shakespeare’s England.

The Theology of King Lear

Saturday, May 5, 2012

2. Disasters in judgment

Lear existed before Shakespeare, as a legendary king of Britain 800 years before Christ. Shakespeare is building on that legend. As the play opens, the aged Lear ("80 years and upwards", he says at one point) wishes to divide his property among his three daughters, but giving the most to the daughter who loves him most. Each is asked to speak. The eldest, Goneril, speaks of her love as "more than word can wield" (I.i.54), etc. The second, Regan, endeavors to surpass her sister, saying that "I profess myself an enemy to all other joys" save "your dear highness' love" (I.i.73-76). (I cite the play's 1997 Arden edition, edited and notated by Foakes. For readers who lose track of the action in the course of what follows, there is a synopsis of the play at the end of this essay.)

The youngest daughter, Cordelia, whom Lear calls "our joy" (I.i.82), i.e. his favorite, says only, "Nothing, my lord" (I.i.87). She does not wish to play this game of flattery. The nihilists have made much of this nothing, which Lear amplifies by adding, "Nothing comes of nothing" (I.i.90), a quote from Deuteronomy. The nihilists see these nothings as a foretaste of the despair to come. But there is an ambiguity. In early 17th century England "nothing" was not just no-thing; it was the Nothing, that about which nothing could be said, as it was beyond human concepts, more, indeed, "than word can yield," in Goneril’s words. It was the God of the Via Negativa of the mystics, the En Sof of the newly popular Kabbalah--the negation of everything that the finite mind could comprehend, the hidden essence of God. Robert Fludd, English physician and alchemist, pictured this original Nothing as a totally black field in his Utriusque Cosmi, Vol. 1 of 1621 (Roob 2001, 104). It is also the prima materia of the alchemists, the original formlessness of matter, of which Thomas Vaughan wrote in 1650, "From this darkness all things have come as from its spring or womb" (1968, 175). One might liken this positive emptiness to the "beginner's mind" of Zen, the way of the simpleton—but one which takes much training to achieve. I will return to this Nothing more than once.

Pressed by her father, Cordelia explains that she loves him "according to my bond" (I.i.93), but half her love must go to her husband when she weds. "Why have my sisters husbands, if they say they love you all?" she challenges (I.i.99-100). Lear's grand retirement ceremony has been spoiled and his kingly authority affronted by Cordelia's apparently cold-hearted reply. He explodes, taking away all Cordelia's inheritance and sundering all ties to her.

Lear's friend and vassal, the Duke of Kent, takes Cordelia's side against Lear, even persisting when Lear tells him to be quiet. For Lear this is treasonous defiance, and Kent's life is forfeit if he persists. When Kent will not desist, Lear banishes him from the kingdom, on pain of death. Then he insinuates to Cordelia’s suitors, who have been waiting in the wings, that she is beneath consideration as a wife. Her dowry will be "nothing" (I.i.247). One might wonder whether this discrediting is not done for the precise reason of keeping her home with him. The Duke of Burgundy declines to woo her. But the young King of France is not deterred: "She is herself a dowry...that art most rich being poor" (I.i.243, 252), he says, turning Lear's evaluation into its opposite. She will be Queen of France.

Lear divides Cordelia's portion among the two older sisters. He also sneaks in a condition--that they support not only him, but also a retinue of a hundred knights--as befitting such devoted daughters, no doubt! The sisters, caught in the rhetoric of their declarations of devotion and the occasion's formality, cannot protest. Later, as the play unfolds, they will renege on their implicit agreement. Then when Lear refuses to accede to their wishes and goes out into a storm, they will lock the gates in case he changes his mind. When it appears that Cordelia is coming to Lear's aid with an army from France, they will respond with armies of their own. Love will turn to war.

In all of this there is an echo of the cult of courtly love, even though it is filial love and not romantic love that is being discussed. (That is part of the problem, in fact.) As the troubadours sang, a man could pledge "all" his love to his Lady, and the Lady could respond in kind. But then the Lady might meet someone else. The faithful one—the poet, of course--would lament his fate and the trust that had been misplaced. An example is this stanza from Cardenal:

Moreover, for Lear to expect a troubadour-like love of a daughter, even ritually, gives it an incestuous quality, for it supposes that father and daughter love each other in the way lovers do. Indeed, what follows, in the intensity of negative feelings, does suggest such a quality in Lear's past treatment of the older daughters; having been taken captive by it, they resent it all the more when they break the illusion. They are all three fostering an emotionally incestuous relationship, one taking advantage of a parent's power and a child's natural love and desire to please. To the extent that the sisters have been victimized by Lear's shadow, as Jung called the part of the personality which a person hides from consciousness, they enact that shadow in relation to him.

It is not inappropriate to see Lear here as symbolizing the power of the patriarchy in Western society, into which women are conditioned from the time they are babies. (By patriarchy I mean systems of domination which hold to the doctrine of the natural superiority of males to rule.) To survive, women must serve this patriarchy, even praise it. Western culture has a repressed anger that erupts when women find themselves with a little power, as women began to have in the 20th century, at a time when brute strength counted for less in the workplace. In Shakespeare's time some women became bloody tyrants when they came to power, as for example Elizabeth's sister, nicknamed "Bloody Mary" for her mass burnings of Protestants. Others, such as her younger half-sister Elizabeth, tried to be different (although Elizabeth in turn killed many Catholics, for conspiring to overthrow the Throne, who were likely guilty only of practicing their faith).

These different images of powerful women influence us as well, at the beginning of the 21st century. Periodically during the 20th century, feminists declared their anger and bitterness at men and wished to take back their power; this anger and its power has led to greater awareness of women's oppression and a few steps forward. It also has led to a stereotype of the angry feminist. At the same time some observers have sensed a change in the new generation of women, who seem embarrassed by their mothers' or older sisters' anger. They seem more at ease, having been born into a culture that has been more affirming of them, even if many inequities remain. The younger generation unconsciously assimilated much less of patriarchy in the first place, so they are not so angry. Similarly, Cordelia as the doted-upon child of Lear's old age neither gives lip-service to Lear nor has repressed anger toward him. She can be straightforward: when she marries she will owe her husband half her love, as is customary. She can also be more forgiving, and even, in filial love, lend him aid when he himself is persecuted.

Lear’s success in turning over management of the kingdom to his daughters and sons-in-law has left him with a new problem: he is without a secure identity. "Who am I, sir?" (I.iv.77) he asks Goneril's steward, for reassurance that he is still the mighty king. The answer, "My Lady's father" (I.iv.78), was not the one Lear wanted. How different Lear's situation is now will be revealed by events, foretold by the gentle warnings of his Fool.

Figure 1. Fool between two wise men. Drawing by Anton Moeller th eElder, 1596.

From the 15th through 17th centuries, the Fool, as the jester to a king or other important person, was a common figure in art and literature. A 1596 Viennese drawing (Fig. 1, above) shows a Fool between two posturing "wise men." "I cannot compete with fools who are eaten up with wisdom," he comments (Tietze-Conrat 1957, 56). Another example (57) is from Hans Holbein's illustrations to the 1515 edition of Erasmus's Praise of Folly. A man looks into a mirror, and the reflection sticks out its tongue (Fig. 2, below). The accompanying text says “Was ever greater folly than self-conceit” (106). In such fashion the fool mirrors his master—or an actor mirrors his audience: Hamlet, after all, counseled the actors to “hold as ‘twere the mirror up to nature” (Ham.III.2.20), meaning human nature.

Figure 2. Fool looking in a mirror. Drawing by Hans Holbein the Younger, illustration in Erasmus, Praise of Folly, 1515 edition, Offentliche Kuntsummlung, Basel.

Lear’s Fool dresses in “motley,” meaning a variety of colors. Costumes with opposing light and dark colors were most typical, a juxtaposition of opposites. Tarot decks offer a suitable illustration with their Fool card (Fig. 3, from the so-called “Swiss” tarot deck; Innes 1978, 63). Lear’s Fool correspondingly plays with a multiplicity of perspectives and the unity of opposites in his very appearance. One such combination is his wisdom, as a wise fool, knowing at least that he is a fool and suggesting that his audience may be fools without such awareness: thus the tarot Fool makes a pair of horns with his left hand, the sign of the cuckold. The Fool contains other opposites as well: He is of lowly stock, yet highly prized by royalty, he is despised by some, yet deeply loved as well. Hamlet, for example, remembers Yorick, his father's fool, with a fondness he gives no other of that generation.

Figure 3. Fool card, "Swiss" tarot deck, late nineteenth century, dressed in motley and giving the sign of the horns with his left hand, signifying the cuckold. Hence the audience is the fool.

The Fool, by occupational definition, is in a position to tell a king things about himself which would, if they were not so cleverly put, be considered insubordination. As Erasmus observes of the fools kept by kings:

Figure 4. A Fool entertaining a king. Drawing by Hans Holbein the Younger, illustration to Erasmus Praise of Follly, 1515, as reprinted in French edition of 1877.

In Jungian terms, the Fool is the one to tell Lear of his shadow. "Who is it that can tell me who I am?" asks Lear (I.iv.221). The Fool replies bravely, "Lear's shadow" (I.iv.222). The surface meaning is that Lear is the shadow of his former self, meaning without the substance he possessed in his property. But shadow also implies what the light does not hit, due to blockages from the persona, or conscious image of oneself; Lear is revealing the side of himself he does not normally expose to others or even admit to himself.

The Fool has available an abundant supply of images to prod Lear into thinking about his actions, which made him the "shadow" of himself. Those who follow Lear, the Fool says, deserve the cockscomb, or fool's cap. When Lear objects, the Fool acts hurt: "Truth," which is what Cordelia and Kent represent, "must to kennel," i.e. be sent away like an ill-favored dog. Yet "Lady Brach"--Lady Bitch, the elder daughters--"may stand by the fire and stink," i.e. be given what they want despite their disgusting ways (I.iv.109-111). Similarly, the Fool riddles that "thou mad'st thy daughters thy mothers." The reason: "Thou gav'st them the rod and putt'st down thine own breeches" (I.iv.163-165). Giving up his power, he has made himself the child, reversing the natural relation. Therefore the Fool sings for sorrow, "That such a king should...go the fools among" (I.iv.169). Lear, and not the Fool, is the fool. The Fool wishes he knew how to lie, but he does not. But Lear values his Fool: "An you liest, sirrah, we'll have you whipped" (I.iv.172).

Soon enough, both Goneril and Regan renege on their agreements. Some of Lear's knights, they say, are disruptive and disrespectful to their hosts' staff. One can imagine that a hundred knights together would be rather rough, and incidents would occur: molesting serving women, cursing, etc. Quite explicitly, when Lear asks his anxious "Who am I?" we see the disguised Kent tripping Goneril's steward, and Lear roaring his approval. (At the same time, Goneril's steward does offend in not addressing Lear as "King" and continuing with mocking facial expressions.)

Just as strong-willed and touchy as their father, the sisters lay down their law to him, in the end saying that not even one of his knights is welcome. When he storms out, they lock the door in case he has second thoughts. The outcome is precisely what the Fool has warned about

When Lear finally storms out, saying he would prefer the cold night air to his daughters' conditions, his inner storm is matched only by the outer one raging around him:

Lear and the Fool wander into the night, soon joined by Lear's two loyal vassals, the Dukes of Kent and Gloucester, and a mad beggar named Tom. The next morning Gloucester, blinded for sympathy with Lear, and the madman (really Gloucester's son fugitive son Edgar, unknown to the father) encounter Lear on the heath, "crowned" with various wildflowers, as Cordelia describes him (IV.iv.iii). He engages in a series of loose associations that would lead any audience to diagnose him mad. Then he turns to the white-bearded Gloucester:

Later in the same interchange, Lear tells the blind Gloucester: “No, do thy worst, blind Cupid, I shall not love” (IV.vi.134). Lear will not love, knowing his love is so blind as to lead to his ruin. But he is now not so blind to himself: he has attained a certain amount of self-knowledge. He has learned that his need for flattery is what did him in, a need that apparently has been satisfied all his life; now, at the end, it makes him a dupe. Formerly blind to the fact that he is not all-powerful, he now has a humbling self-recovery through self-knowledge. Shakespeare even tells us in advance that the issue is self-knowledge, when he has Regan remark to Goneril that Lear "hath ever but slenderly known himself" (I.i.294-295). To be sure, even now he does not acknowledge his part in the affair, namely his throwing in the condition of the hundred knights, taking all objections to them as a personal affront, and insisting that they are all well-behaved. But he has indeed gained something precious from his "nothing," from his ignorance and powerlessness: self-knowledge. In that sense he could take consolation from another stanza of Cardenal's song on betrayed love:

I never won anything so great Anc non gazamhei tan gran re

As when I lost my mistress; Con quam perdei ma mia;

In losing her, I won back myself, Quar, perden leis, gazanhei me,

When she had won me over. Qu’il gazainhat m’avia.

He wins little who loses himself, Petit gazainha qui pert se,

But if one loses that which does one harm, Mas qui pert so que dan li te,

I think that it’s a gain. Ieu cre que gazainhs sia.

(Press 1971, 283-285)

This "myself" which Lear has won thus far is knowledge of the Jungian shadow, the part of oneself hidden from the conscious ego. But knowledge of that part leads one to more, toward what Jung, following ancient Hindu teachings, calls the Self. Lear is on his way.

The youngest daughter, Cordelia, whom Lear calls "our joy" (I.i.82), i.e. his favorite, says only, "Nothing, my lord" (I.i.87). She does not wish to play this game of flattery. The nihilists have made much of this nothing, which Lear amplifies by adding, "Nothing comes of nothing" (I.i.90), a quote from Deuteronomy. The nihilists see these nothings as a foretaste of the despair to come. But there is an ambiguity. In early 17th century England "nothing" was not just no-thing; it was the Nothing, that about which nothing could be said, as it was beyond human concepts, more, indeed, "than word can yield," in Goneril’s words. It was the God of the Via Negativa of the mystics, the En Sof of the newly popular Kabbalah--the negation of everything that the finite mind could comprehend, the hidden essence of God. Robert Fludd, English physician and alchemist, pictured this original Nothing as a totally black field in his Utriusque Cosmi, Vol. 1 of 1621 (Roob 2001, 104). It is also the prima materia of the alchemists, the original formlessness of matter, of which Thomas Vaughan wrote in 1650, "From this darkness all things have come as from its spring or womb" (1968, 175). One might liken this positive emptiness to the "beginner's mind" of Zen, the way of the simpleton—but one which takes much training to achieve. I will return to this Nothing more than once.

Pressed by her father, Cordelia explains that she loves him "according to my bond" (I.i.93), but half her love must go to her husband when she weds. "Why have my sisters husbands, if they say they love you all?" she challenges (I.i.99-100). Lear's grand retirement ceremony has been spoiled and his kingly authority affronted by Cordelia's apparently cold-hearted reply. He explodes, taking away all Cordelia's inheritance and sundering all ties to her.

Lear's friend and vassal, the Duke of Kent, takes Cordelia's side against Lear, even persisting when Lear tells him to be quiet. For Lear this is treasonous defiance, and Kent's life is forfeit if he persists. When Kent will not desist, Lear banishes him from the kingdom, on pain of death. Then he insinuates to Cordelia’s suitors, who have been waiting in the wings, that she is beneath consideration as a wife. Her dowry will be "nothing" (I.i.247). One might wonder whether this discrediting is not done for the precise reason of keeping her home with him. The Duke of Burgundy declines to woo her. But the young King of France is not deterred: "She is herself a dowry...that art most rich being poor" (I.i.243, 252), he says, turning Lear's evaluation into its opposite. She will be Queen of France.

Lear divides Cordelia's portion among the two older sisters. He also sneaks in a condition--that they support not only him, but also a retinue of a hundred knights--as befitting such devoted daughters, no doubt! The sisters, caught in the rhetoric of their declarations of devotion and the occasion's formality, cannot protest. Later, as the play unfolds, they will renege on their implicit agreement. Then when Lear refuses to accede to their wishes and goes out into a storm, they will lock the gates in case he changes his mind. When it appears that Cordelia is coming to Lear's aid with an army from France, they will respond with armies of their own. Love will turn to war.

In all of this there is an echo of the cult of courtly love, even though it is filial love and not romantic love that is being discussed. (That is part of the problem, in fact.) As the troubadours sang, a man could pledge "all" his love to his Lady, and the Lady could respond in kind. But then the Lady might meet someone else. The faithful one—the poet, of course--would lament his fate and the trust that had been misplaced. An example is this stanza from Cardenal:

Giving myself, at her mercy I put Donan me, mes en sa merceIn our play, Lear takes on this role of the betrayed. His elder daughters' words were just poems, expressions within the framework of the conventions of courtly love. But Lear has given more than sentiments to his daughters: he has given them his lands, the source of his worldly power. How could Lear have taken the pledges so seriously? Perhaps getting his daughters' love-pledges was a way to prevent them from arguing with his demand later for his knights. He sought to trap his daughters, failing to see that his daughters could also trap him. When that happens, Lear laments in fine troubadour style. It is a game of entrapment that Cordelia refuses to play.

Myself, my heart and my life-- Mi, mon cor, e ma via--

Hers, who casts me aside De leis, que.m vir’e.m desmante

And abandons and changes me for another! Per autrui, e.m cambia!

He who gives more than he keeps Qui dona mais que non rete

And loves another more than himself Et ama mais autrui que se,

Chooses a bad deal, Chauzis avol partia,

Since he has no care or thought for himself, Quan de se no.ilh cal ni.l sove,

But forgets himself E per aco s’oblia For that which profits him not. Que pro no.ilh te. (Press 1971, 283)

Moreover, for Lear to expect a troubadour-like love of a daughter, even ritually, gives it an incestuous quality, for it supposes that father and daughter love each other in the way lovers do. Indeed, what follows, in the intensity of negative feelings, does suggest such a quality in Lear's past treatment of the older daughters; having been taken captive by it, they resent it all the more when they break the illusion. They are all three fostering an emotionally incestuous relationship, one taking advantage of a parent's power and a child's natural love and desire to please. To the extent that the sisters have been victimized by Lear's shadow, as Jung called the part of the personality which a person hides from consciousness, they enact that shadow in relation to him.

It is not inappropriate to see Lear here as symbolizing the power of the patriarchy in Western society, into which women are conditioned from the time they are babies. (By patriarchy I mean systems of domination which hold to the doctrine of the natural superiority of males to rule.) To survive, women must serve this patriarchy, even praise it. Western culture has a repressed anger that erupts when women find themselves with a little power, as women began to have in the 20th century, at a time when brute strength counted for less in the workplace. In Shakespeare's time some women became bloody tyrants when they came to power, as for example Elizabeth's sister, nicknamed "Bloody Mary" for her mass burnings of Protestants. Others, such as her younger half-sister Elizabeth, tried to be different (although Elizabeth in turn killed many Catholics, for conspiring to overthrow the Throne, who were likely guilty only of practicing their faith).

These different images of powerful women influence us as well, at the beginning of the 21st century. Periodically during the 20th century, feminists declared their anger and bitterness at men and wished to take back their power; this anger and its power has led to greater awareness of women's oppression and a few steps forward. It also has led to a stereotype of the angry feminist. At the same time some observers have sensed a change in the new generation of women, who seem embarrassed by their mothers' or older sisters' anger. They seem more at ease, having been born into a culture that has been more affirming of them, even if many inequities remain. The younger generation unconsciously assimilated much less of patriarchy in the first place, so they are not so angry. Similarly, Cordelia as the doted-upon child of Lear's old age neither gives lip-service to Lear nor has repressed anger toward him. She can be straightforward: when she marries she will owe her husband half her love, as is customary. She can also be more forgiving, and even, in filial love, lend him aid when he himself is persecuted.

Lear’s success in turning over management of the kingdom to his daughters and sons-in-law has left him with a new problem: he is without a secure identity. "Who am I, sir?" (I.iv.77) he asks Goneril's steward, for reassurance that he is still the mighty king. The answer, "My Lady's father" (I.iv.78), was not the one Lear wanted. How different Lear's situation is now will be revealed by events, foretold by the gentle warnings of his Fool.

Figure 1. Fool between two wise men. Drawing by Anton Moeller th eElder, 1596.

From the 15th through 17th centuries, the Fool, as the jester to a king or other important person, was a common figure in art and literature. A 1596 Viennese drawing (Fig. 1, above) shows a Fool between two posturing "wise men." "I cannot compete with fools who are eaten up with wisdom," he comments (Tietze-Conrat 1957, 56). Another example (57) is from Hans Holbein's illustrations to the 1515 edition of Erasmus's Praise of Folly. A man looks into a mirror, and the reflection sticks out its tongue (Fig. 2, below). The accompanying text says “Was ever greater folly than self-conceit” (106). In such fashion the fool mirrors his master—or an actor mirrors his audience: Hamlet, after all, counseled the actors to “hold as ‘twere the mirror up to nature” (Ham.III.2.20), meaning human nature.

Figure 2. Fool looking in a mirror. Drawing by Hans Holbein the Younger, illustration in Erasmus, Praise of Folly, 1515 edition, Offentliche Kuntsummlung, Basel.

Lear’s Fool dresses in “motley,” meaning a variety of colors. Costumes with opposing light and dark colors were most typical, a juxtaposition of opposites. Tarot decks offer a suitable illustration with their Fool card (Fig. 3, from the so-called “Swiss” tarot deck; Innes 1978, 63). Lear’s Fool correspondingly plays with a multiplicity of perspectives and the unity of opposites in his very appearance. One such combination is his wisdom, as a wise fool, knowing at least that he is a fool and suggesting that his audience may be fools without such awareness: thus the tarot Fool makes a pair of horns with his left hand, the sign of the cuckold. The Fool contains other opposites as well: He is of lowly stock, yet highly prized by royalty, he is despised by some, yet deeply loved as well. Hamlet, for example, remembers Yorick, his father's fool, with a fondness he gives no other of that generation.

Figure 3. Fool card, "Swiss" tarot deck, late nineteenth century, dressed in motley and giving the sign of the horns with his left hand, signifying the cuckold. Hence the audience is the fool.

The Fool, by occupational definition, is in a position to tell a king things about himself which would, if they were not so cleverly put, be considered insubordination. As Erasmus observes of the fools kept by kings:

They can speak truth and even open insults and be heard with positive pleasure; indeed, the words which would cost a wise man his life are surprisingly enjoyable when uttered by a clown. For truth has a genuine power to please if it manages not to give offence, but this is something the gods have granted only to fools.(1971, 119)Holbein has an illustration for this passage, a fool standing in front of a king, smiling yet facing him down with his tongue out (Fig. 4; Erasmus 1877, 108). Lear's Fool, in conformity with this characterization, tells Lear things that he does not want to believe about himself, but does so in such amusing terms that Lear cannot think to punish him.

Figure 4. A Fool entertaining a king. Drawing by Hans Holbein the Younger, illustration to Erasmus Praise of Follly, 1515, as reprinted in French edition of 1877.

In Jungian terms, the Fool is the one to tell Lear of his shadow. "Who is it that can tell me who I am?" asks Lear (I.iv.221). The Fool replies bravely, "Lear's shadow" (I.iv.222). The surface meaning is that Lear is the shadow of his former self, meaning without the substance he possessed in his property. But shadow also implies what the light does not hit, due to blockages from the persona, or conscious image of oneself; Lear is revealing the side of himself he does not normally expose to others or even admit to himself.

The Fool has available an abundant supply of images to prod Lear into thinking about his actions, which made him the "shadow" of himself. Those who follow Lear, the Fool says, deserve the cockscomb, or fool's cap. When Lear objects, the Fool acts hurt: "Truth," which is what Cordelia and Kent represent, "must to kennel," i.e. be sent away like an ill-favored dog. Yet "Lady Brach"--Lady Bitch, the elder daughters--"may stand by the fire and stink," i.e. be given what they want despite their disgusting ways (I.iv.109-111). Similarly, the Fool riddles that "thou mad'st thy daughters thy mothers." The reason: "Thou gav'st them the rod and putt'st down thine own breeches" (I.iv.163-165). Giving up his power, he has made himself the child, reversing the natural relation. Therefore the Fool sings for sorrow, "That such a king should...go the fools among" (I.iv.169). Lear, and not the Fool, is the fool. The Fool wishes he knew how to lie, but he does not. But Lear values his Fool: "An you liest, sirrah, we'll have you whipped" (I.iv.172).

Soon enough, both Goneril and Regan renege on their agreements. Some of Lear's knights, they say, are disruptive and disrespectful to their hosts' staff. One can imagine that a hundred knights together would be rather rough, and incidents would occur: molesting serving women, cursing, etc. Quite explicitly, when Lear asks his anxious "Who am I?" we see the disguised Kent tripping Goneril's steward, and Lear roaring his approval. (At the same time, Goneril's steward does offend in not addressing Lear as "King" and continuing with mocking facial expressions.)

Just as strong-willed and touchy as their father, the sisters lay down their law to him, in the end saying that not even one of his knights is welcome. When he storms out, they lock the door in case he has second thoughts. The outcome is precisely what the Fool has warned about

Fool. [to Lear] I marvel what kin thou and thy daughters are. They’ll have me whipped for speaking true, thou’lt have me whipped for lying, and sometimes I am whipped for holding my peace. I had rather be any kind o’thing but a fool, and yet I would not be thee, nuncle. Thou hast pared thy wit o’both sides and left nothing i’the middle. (I.iv.173-179) [Note: comments in italics at the start of a speech are mine to clarify the context]Again the "nothing." The Fool had alluded to it once before, when Lear had dismissed the Fool's words as "nothing." "Can you make no use of nothing?" the Fool replied (I.iv.128-129). Lear thought not, repeating his "Nothing comes of nothing" proverb that he had used with Cordelia. The Fool then had a witty rejoinder, to Kent: "So much will the rent from his land come to" (I.iv.132-133). But it is a good question: What creative use derives from nothing?--meaning both what another says that one dismisses as nonsense, and one's lack of power. The tarot Fool, along these lines, is unnumbered and often by default is given the number zero.

When Lear finally storms out, saying he would prefer the cold night air to his daughters' conditions, his inner storm is matched only by the outer one raging around him:

Lear. ...In such a nightWe cringe here at Lear's calling himself "kind," remembering how he treated Cordelia. But he did give Goneril and Regan all, and his trust has indeed been misplaced, just as the Fool foretold.

To shut me out! Pour on! I will endure

In such a night as this! O Regan, Goneril,

Your old kind father, whose heart gave you all--

O, that way madness lies, let me shun that;

No more of that. (III.iv.17-22)

Lear and the Fool wander into the night, soon joined by Lear's two loyal vassals, the Dukes of Kent and Gloucester, and a mad beggar named Tom. The next morning Gloucester, blinded for sympathy with Lear, and the madman (really Gloucester's son fugitive son Edgar, unknown to the father) encounter Lear on the heath, "crowned" with various wildflowers, as Cordelia describes him (IV.iv.iii). He engages in a series of loose associations that would lead any audience to diagnose him mad. Then he turns to the white-bearded Gloucester:

Lear. Ha! Goneril with a white beard? They flattered me like a dog, and told me I had the white hairs in my beard ere the black ones were there [when I was a child]. To say "ay" and "nay" to everything that I said "ay" and "nay" to was no good divinity [theology]. When the rain came to wet me once, and the wind to make me chatter; when the thunder would not peace at my bidding; there I found 'em, there I smelt 'em out. Go to! They are not men o'their words; they told me I was everything; 'tis a lie, I am not ague-proof [immune to shivering, or fever]. (IV.vi.96-104) [Note: comments within a speech are from editors' notes to the play, from either the Riverside edition or one or the other of the Arden editions]Erasmus, in Praise of Folly, had said the same: “And for all their good fortune princes seem to me to be particularly unfortunate in having no one to tell them the truth and being obliged to have flatterers for friends” (1971, 118).

Later in the same interchange, Lear tells the blind Gloucester: “No, do thy worst, blind Cupid, I shall not love” (IV.vi.134). Lear will not love, knowing his love is so blind as to lead to his ruin. But he is now not so blind to himself: he has attained a certain amount of self-knowledge. He has learned that his need for flattery is what did him in, a need that apparently has been satisfied all his life; now, at the end, it makes him a dupe. Formerly blind to the fact that he is not all-powerful, he now has a humbling self-recovery through self-knowledge. Shakespeare even tells us in advance that the issue is self-knowledge, when he has Regan remark to Goneril that Lear "hath ever but slenderly known himself" (I.i.294-295). To be sure, even now he does not acknowledge his part in the affair, namely his throwing in the condition of the hundred knights, taking all objections to them as a personal affront, and insisting that they are all well-behaved. But he has indeed gained something precious from his "nothing," from his ignorance and powerlessness: self-knowledge. In that sense he could take consolation from another stanza of Cardenal's song on betrayed love:

I never won anything so great Anc non gazamhei tan gran re

As when I lost my mistress; Con quam perdei ma mia;

In losing her, I won back myself, Quar, perden leis, gazanhei me,

When she had won me over. Qu’il gazainhat m’avia.

He wins little who loses himself, Petit gazainha qui pert se,

But if one loses that which does one harm, Mas qui pert so que dan li te,

I think that it’s a gain. Ieu cre que gazainhs sia.

(Press 1971, 283-285)

This "myself" which Lear has won thus far is knowledge of the Jungian shadow, the part of oneself hidden from the conscious ego. But knowledge of that part leads one to more, toward what Jung, following ancient Hindu teachings, calls the Self. Lear is on his way.

3. Lear and the Gnostic demiurge

Cardenal continues his song on the theme of betrayed love:

Those last two lines also suggest that more may be at stake than romantic love, or even love between parent and child: The object of love is a "that which" (“so qu’,” short for “so que”) instead of a "she who." In such a case, "that which ill behooves him" could be a religion or an ideology as much as a person. Cardenal's medieval editors say that as a youth he had been a canon in the Catholic Church. One might wonder whether he might be blasting his excessive devotion and trust in that institution, given what it did later to the people and culture of his land. Perhaps when the Cathars were first attacked he distanced himself from them--that is, sought to "quit and distrust that which he ought to love," in the words of the song. In a world where suspicion of heresy could lead to imprisonment and dispossession of one's property at least, it was best not to be specific, and to let one's hearers interpret the moral themselves.

Such a perspective suggests another level in interpreting Lear's story. Lear's elder daughters, like most of those around him, had praised him as a god, in fact the god of Plato and orthodox Christianity, so perfect as to be beyond words and to whom other love is subordinate. Once humbled, Lear sees such praise as "no good divinity" (Iv.vi.99-100). On the level of divinity, this tale is not only about families, but about a social structure, patriarchal or not, that demands to be held in awe and lashes out when its evils and vulnerabilities are exposed.

But there is more here even than politics. It is a critique of any religion that sacrelizes that style of rule. What I see in Shakespeare here, as in Cardenal, is an echo of Gnosticism, specifically, its critique of the jealous God of the Hebrew Bible, whom the Gnostics called by various names: e.g. Yaldabaoth, Error, and demiurge. The word “demiurge,” meaning craftsman or artificer, came from Plato’s Timaeus, in which he imagined a lower level god doing the work of making the world, following patterns laid out by a higher god. For the Gnostics, such a craftsman was a highly imperfect one, a maker of counterfeits. The Cathars, the remnant of Gnosticism in the Middle Ages, carried on this tradition and denounced the God of the Catholic and Orthodox Churches as a “dieu etranh,” an alien god, as opposed to the “dieu juste,” the true god whom they worshiped (Nelli 1976, 38-39).

In Shakespeare's day, kings were seen as being to their lands what God was to his creation; kings ruled as the image of Providence. Lear's acts at the beginning of the play mimic those of the god of Genesis. First comes the void, Lear’s “nothing.” From this nothing came everything, the opposite of Lear’s maxim Next, the god divided light from dark and above from below; similarly, Lear divides his kingdom. In Lear's case, he is unintentionally creating disorder out of order, the reverse of Genesis (Calderwood 1987). Soon enough, we see the god of Genesis in Lear’s curses, first at Cordelia, then at Kent, and finally at his elder daughters. What is this but the same reaction to disobedience that Jehovah exhibits, cursing the beings that he has created in his image, first Eve, then Adam, then Cain, then all humanity except Noah and his family?

Later, in his "madness," Lear sees his earlier self as ungodly, “no good divinity.” Yet it is not that he saw the god of Genesis wrongly; rather, he sees the shortcomings of that god as embodied in himself. Now he is becoming Gnostic; for orthodox Christianity accepts even the god of Genesis as the one true god. This is where his, and Shakespeare's, insight lies, Gnostic in the very specific sense of the summaries contained in the polemical writings of Irenaeus and the ancient texts that correspond to them.

The Gnostics argued that the orthodox Judeo-Christian god--and by implication any institution modeling itself after that God--could not be the true god because of his faults--e.g. blatant favoritism, rages, and cruelty toward people who defied him (Williams 1996, Chapter 1). Gnostic texts called him arrogant, blind (in the sense of ignorant), and foolish. An example is from the Apocryphon (i.e. Secret Book) of John, one of a group of texts found in Egypt in 1945:

Yaltabaoth (also spelled "Yaldabaoth") means "Father of Abaoth," according to Rudolph (1983) a reference to Sabaoth, mentioned by several texts as the demiurge's son. “Child of chaos” is another possibility (Quispel 1965, 75). Another text, The Origin of the World, says that the name means "Child, pass through to here," words spoken by his mother Pistis Sophia (Faithful Wisdom) when he emerged from "the abyss," “chaos,” or "shadow" that she had caused to exist outside "the eternal realm of truth" (Robinson 1988, 173).

"Saklas" means "fool" in Hebrew (Barnstone 1984, 75). "Samael," The Origin of the World says, means "blind god" (Robinson 1988, 175). (In Judaism, it was also a name for Satan.) He is arrogant in that he thinks he is the source of all power: Another characteristic is his ignorance: "He is ignorant of his strength, the place from which he had come." The demiurge also declares 'I am a jealous god" (112), he will countenance no other gods, reminding us again of the god of Genesis and Moses.

The texts attribute these four characteristics to the God of Genesis: foolishness, blindness, arrogance, and jealousy. All these labels apply abundantly to Lear. We have already seen how the Fool has implicitly been telling Lear he is a fool. To make the point explicit, Shakespeare has Lear himself ask the Fool: "Are you calling me fool, boy?" (I.iv.141); the Fool replies, "Thou hast given away all thy other titles; that thou wast born with" (I.iv.142-143). Later Lear applies this label to himself: "I am the natural fool of fortune" (IV.vi.195).

As for blindness in the sense of ignorance, the idea is implicit in a remark that Gloucester, Lear's same-age friend, makes after being literally blinded by Lear’s son-in-law: "I stumbled when I saw," (IV.1.21), meaning that he was blind to who was good and who was evil. Sight vs. blindness is also the dominant image in an early exchange between Kent and Lear, when. Kent objects to his treatment of Cordelia. When Lear orders him out of his sight, Kent replies: "See better, Lear" (I.i.159), implying Lear’s blindness to what he is doing. When Lear then swears by Apollo, god of light, Kent replies, "Thou swear'st thy gods in vain" (I.i.162).

Lear’s arrogance is evident in his treatment first of Cordelia, who refuses to pledge all her love to Lear, and then Kent, who says Lear is being too harsh toward Cordelia. He thinks he knows everything, and he lashes out at anybody contradicting him.

As for Lear's jealousy, by disinheriting Cordelia he hopes to prevent her marriage, which would mean her departure from him. And like Juliet's father in Romeo and Juliet, he is jealous of any authority she follows other than his, including her own.

The Gnostics’ prime example of Jehovah’s display of these traits is his behavior in the Garden of Eden. Having created the first humans, Jehovah—or Ialdabaoth, as the texts call him--wants total, unquestioning obedience. When they immediately disobey, following the teachings of the serpent, Ialdabaoth takes away their immortality and throws them out. They will have to fend for themselves. But he demands absolute worship even then, sending a flood to destroy humanity when they are insufficiently devout. When Moses later kills the devotees of the Golden Calf, he is only following his mentor’s example, and providing a model for Christian kings to follow.

When Lear disinherits Cordelia and banishes Kent, he is only following the example of the God of Genesis. In orthodox Christianity, the sin is all Adam and Eve’s. In Shakespeare, obviously, Cordelia and Kent are the good guys and Lear the vain fool. Gnostic Christianity and Shakespeare are on the same side. Actually, since Cordelia is the instigator of both Kent’s and her disobedience, she is not only Eve, but also the serpent. Like Eve and the serpent for the Gnostics, she does no wrong. In the texts, the serpent is the divine feminine principle, the Epinoia, or after-thought, who instructs Eve. The Apocryphon of John says, "The Epinoia appeared as a light and she awakened their thinking" (Robinson 1988, 118). And the Hypostasis of the Archons: "The female spiritual principle came in the snake, the instructor" (164).

Shakespeare could not have read these texts: they were buried underground near Hag Hammadi, Egypt, until 1945. Yet he could have derived the basic ideas from a critical reading of Irenaeus’s “exposure” of the sects he says called themselves Gnostic. One is the “Ophites,” meaning “serpent worshipers.” They give the name “Ialdabaoth” to the lower-order creator-god, just as in the original texts we have been examining. In Irenaeus’s summary, he is considered arrogant, jealous, and “surrounded” by “forgetfulness” (Barnstone 1984, 662), i.e. ignorant of his origin.

As Iranaeus relates, Ialdabaoth is the eldest of seven rulers born of Lower Wisdom. They make a human being, but it has an inner power and luminescence that they lack. Ialdabaoth tries to pull that power out of Adam, and that is the creation of Eve. The rulers satisfy their “desire” on her, but Lower Wisdom has already taken the power out of Eve. Iranaeus continues:

Another group of Gnostics makes the connection to Sophia even clearer. Irenaeus says,

Then, as in Genesis, comes the expulsion from Paradise, and later the flood. In the Ophites’ telling of the story, according to Irenaeus, it is Sophia, the friend of humanity, who tells Noah to build the ark; Jehovah is bent on destroying his creation once and for all! Irenaeus’s purpose in telling all this is to expose the ones making up such stories as deceitful liars and scoundrels. Yet for one who values stories as stories, and not as historical truths, the Gnostic version puts an ironic twist on Genesis and its God. An attentive reader such as Shakespeare, who no doubt was not all that fond of being ordered and threatened by blustering, idiotic authorities himself, could, had his eyes fallen on these pages, hardly have missed a critique here of a certain personality type—today some call it “type A”; but in days gone by it was simply Jehovah, Lord of Hosts.

Moreover the exact story that Irenaeus is criticizing occurs in the Old Testament text Wisdom of Solomon, in a passage (10:4) in which Sophia, God’s Wisdom, is shown saving the day after Jehovah initiates actions that could destroy his chosen species once and for all:

In the play, we get the critique of this Jehovah-personality-type not only in Lear, but also in the other old authoritarian in the story, Lear’s friend Gloucester. He, too, has good and bad offspring, in his case two sons, and is fooled by the bad Edmund while rejecting and persecuting the good Edgar. In his case the bad one is exceptionally devilish, and Gloucester trusts his offspring. Once taken in, he too, is savagely ruthless. When Edmund fools his father into thinking that Edgar wounded him when he tried to apprehend Edgar, the father says, “Bring the murderous coward to the stake [Foakes’ note: place of execution]:/ He that conceals him, death!” (II.i.61-62). Gloucester, too, in the end comes to recognize his error, although not until Edmund’s friends have put out his eyes: “I stumbled when I saw,” (IV.i.21) he laments.

Shakespeare’s device of the good and bad offspring occurs occasionally in Genesis, as with Cain and Abel. It is one the Gnostics use extensively. In the Ophite myth, according to Irenaeus, Ialdabaoth looked down upon the mire of material substance and with it bore a son, a kind of twisted spirit, who in turn begot seven evil spirits. This description corresponds somewhat to Gloucester’s begetting of his bastard Edmund, out of wedlock yet “saucily” (I.i.20), i.e. with lust. For the Ophites, the good son is Jesus, born of the Virgin and begotten by Ialdabaoth, unwittingly acting in accord with Sophia’s plan. The Christ then descends upon Jesus at the baptism. Christ the son of the highest God, and Jesus son of Ialdabaoth, merge at the baptism. This son, of course, corresponds to Edgar, Gloucester’s legitimate son. Just as Ialdabaoth, through the Jewish Saducees, persecutes Jesus, so does Gloucester, deceived by Edmund, go after Edgar, who at first is gullible like his father but later learns from his experience.

Other Gnostic myths have variations on this theme. Irenaeus summarizes the myth told by Ptolemaeus, a follower of the arch-heretic Valentinus. In this myth the Highest God begets the good Sophia, Sophia begets the so-so demiurge, and the demiurge begets Satan. For another example, in Hypostasis of the Archons, the demiurge himself is the bad son, engendered by the good Sophia, while the good son is Sabaoth, engendered by Ialdabaoth.

The ultimate fate of Ialdabaoth, or the demiurge, likewise varies. The variations correspond to the variety of outcomes for the personality-type. In Hypostasis of the Archons, Yaldabaoth is “thrown down to Tartarus” (Robinson 1988, 158) by Sophia, who raises his son Sabaoth to the seventh heaven. In Ptolemaeus, when the demiurge hears the Savior he receives him gladly, even if still without knowledge of the higher realm. For the Ophites, after the resurrection Ialdabaoth stops persecuting Jesus, and after the ascension sets him at his right hand. There Jesus receives souls; he takes those with gnosis to himself and gives those with faith and good works to Ialdabaoth. It is not clear exactly what happened between the crucifixion and the resurrection to change Ialdabaoth’s mind. We shall see the process of enlightenment is in later sections of this essay, using other Gnostic sources as a guide and Lear and Gloucester as examples.

The texts found in Egypt add feeling to Irenaeus’s rather lifeless summaries. One of the most poetic is the Gospel of Truth, in which the creator god is called “Error.” (Oddly, the word takes a feminine pronoun; perhaps that is only because it is a feminine noun in Greek, plane. Its characterization fits the normally masculine demiurge far better than it does Sophia, the only feminine candidate. The English translator uses the neutral “it.”):

In the play, we see the anguish first in those whom Lear ignorantly and terrifyingly persecutes, Cordelia and Kent. Then Lear's older daughters inflict the terror on Lear, one that expands to include others: after Lear, there is the Fool, and after him. Gloucester; even Cordelia near the end is not exempt from anguish and terror. As though with the Gospel of Truth's imagery in mind, in Olivier's film of the play a thick fog blankets the land after Lear leaves Goneril to visit Regan.

Error’s triumph is the creation, “preparing in power and beauty the substitute for the truth.” The beauty of the created world is not in question; what is in question is its goodness and its creation by the highest god. However beautiful, it is grossly imperfect, a world whose creatures live by killing one another. Similarly human rulers sometimes sponsor great art projects to cover up their uglier deeds (e.g. Athens in its war against Sparta, Rome during the Empire). But that is simply part of the deceit, not something that speaks in his favor.

Error's being "brought to naught" is like the fate of Ialdabaoth in Hypostasis of the Archons, who is said not to have repented of his arrogance and was therefore sent to Tartarus, like the Christian Satan. The Gospel of Truth adds, "They were nothing, the anguish and the terror and the creature of deceit," meaning Error; therefore "Despise Error." Error prepared "works and oblivions and terrors, in order that by means of those it might entice those of the middle and capture them" (all Robinson 1988, 40). The "middle" here is the place of souls lacking gnosis but still wanting salvation--souls called psychica (ensouled) in some texts (Attridge 1985, Vol. 2, 46). By such means the demiurge hopes to keep these souls from attaining knowledge, and so trap them in its realm.

Later in the Gospel of Truth, Error sounds even more like the Devil: "When knowledge drew near it--this is the downfall of (Error) and all its emanations [i.e. spirits it produced]--Error is empty, having nothing inside" (44). In such a state, presumably, it loses its allure. This is the fate of a Satanic demiurge, a false god unwilling to admit its deceptions and self-deceptions.

What corresponds in the play to Error’s downfall is not Lear's end but rather that of his older daughters and Gloucester’s son Edmund. Edgar defeats Edmund in single combat and presents evidence of his crimes. At the same time, Edgar confronts Goneril in front of her husband with letters Regan and she have written to Edmund. The dying Edmund admits his crimes and even adds, “Some good I mean to do” (V.iii.241)—he wants to cancel his order to have Lear and Cordelia murdered. As for Goneril, she kills her sister Regan and then herself. Even they are victims. One Valentinian text, the Tripartite Tractate, gives an apt and quite modern name for what has seduced them: "lust for power" (Robinson 1988, 84f).

But their dying is not the important thing, for the same happens to Lear and Cordelia. What matters is the exposure of their "emptiness," thus neutralizing their ability to "entice" those in the middle—for example Goneril's husband and the rest of the British army, who thought they were fighting off a French invasion, not supporting a coup d’etat. This emptiness is something the evil characters do not recognize in themselves until it is too late: instead, they dream of power and glory, and see others' anguish and terror as a means to that end.

Lear early on loses his illusions of power; he is forced to face the anguish head on. In this he represents the demiurge with another outcome, in a variant told in many Gnostic texts. Like Lear, the demiurge in such texts is a ruler “not inclined to evil” (Robinson 1988, 88) but unfortunately influenced by “lust for power” (84).

There is much about Error that is reminiscent of the play's emphasis on the word "nothing." The anguish, terror, and fear of oblivion are "nothing"; they are products of ignorance and deceit. Error is "empty"; inside it is "nothing." Its place of origin, in The Origin of the World, is shadow and the abyss. This nothing is still very much something, but a something whose home appears to be below everything, as opposed to the nothing that is above everything, the fullness.

All of this shows the play’s undeniable moral thrust, hardly nihilistic in its vision. Lear and Gloucester, the foolish old men, take a different path, one which again Gnostic myth expresses well. The Gnostic teacher Basilides, in an account unknown until the mid-19th century, probably comes the closest to expressing the demiurge’s outcome in terms similar to Lear’s. We shall see in the next section that the essence of this account continued in the alchemists, one place Shakespeare could have found it.

Basilides, like many other Gnostics, calls the demiurge “the Seven,” which could mean either the seventh planet, Saturn, which rules the rest, or a power beyond Saturn that rules all seven planets. Since the Jews worshiped on Saturday, the Graeco-Roman world in which Basilides lived tended to identify Jehovah with Saturn. Saturn is the Graeco-Roman sky-god so consumed with fear of being overthrown that he devours all his children, missing only Jupiter, who does later overthrow him. In Rome the overthrow of the old year by the new, the hunched-up old man by the babe, was celebrated in the Saturnalia. Similarly, for Gnostics, the Christ child replaced the tribal god Jehovah. We can see in Lear some of the characteristics, often associated with old age, that even today are called "saturnine": a melancholy bitterness, rage toward those who will not cater to one, and an ironic sense of humor, which the Fool appeals to. In Roman myth, the deposed Saturn was in charge of the Elysian Fields, where dead war heroes went. Lear's insistence on his hundred knights might be his attempt to play that role. We shall see in the next section how seeing Lear as Saturn allows us to find Lear's process in certain alchemical works.

In Basilides’ myth, however, the demiurge is not overthrown; he gets a new perspective. Basilides describes the conversion of the demiurge in terms quite reminiscent of our play. Let me first explain Basilides' conception of the highest god, “the God of all.” Basilides calls it the "nonexistent god," so removed from our world that it cannot be described in words. One can truly say neither that it exists nor that it does not exist; it is the No-thing beyond everything that brings about further No-things (to use Lear’s phrase), its ineffable Sonships, as well as the created world. And although it never acts in the world, what happens there is in accord with its plan, for good and for ill. Thus a demiurge emerges, actually two of them, one called “the Eight” to rule the stars and the other to rule the planets. Although the demiurges each think initially that they are the god of all, the sons teach them otherwise:

To the extent that this myth describes the transformation of an individual human being's view of ego, Self, and world, Lear's awakening from his habit of deifying himself corresponds to just such an event, as he becomes humbled by his elder daughters and the storm.

Basilides mentions a Christ, but it is a Christ in the heavens, rather like the “preexistent Logos” in the Gospel of John. Basilides’ heavenly Christ is the model for the one on earth, whom he calls "Jesus the son of Mary," who "was illuminated and set on fire by the light which shone upon him"--apparently while still in the womb, for the light goes “as far as Mary” (Barnstone 1984, 633). Jesus then gathers the "Sonship"--"seeds" (630) of the non-existent god within matter--around him, which "ascends above after being purified" (633).

We shall discuss this "purification," as alchemy applied it to humanity, in the next section. For now I wish to ask, Who is Lear's instructor, corresponding to Basilides' Christ? There does not have to be one, of course: we are using Gnostic texts piecemeal to illuminate the play; there is no allegory tying each element of the play to an element of a Gnostic myth. Yet much has been written about Christ-figures in Lear, in the sense of instructors and redeemers.

Suggestions of Christ occur by way of Biblical allusions to the Christ of the canonical Gospels. Shaheen (1988) summarizes many of the references. First, at least three allusions to Christ occur in descriptions of Cordelia, thus suggesting Cordelia as Christ-like redeemer of her father. There is the King of France's homage to her when he asks her to be his wife, without dowry or father's blessing. France addresses her: "Fairest Cordelia, that art most rich being poor/ Most choice forsaken and most loved despised" (I.i.250-251). These words echo Paul's descriptions of Christ , e.g. "though he was rich, yet for your sake he became poor" (II Cor. 8:9), and Isaiah’s words then taken as prophecies of Christ: “We desired him, despised as he was and the least of men.” (Is.53:2-3). Erasmus had called attention to these antithetical descriptions in a much-reprinted essay, “Sileni Alcibiadis” (1992, 264; Gatti, 1989, sees another part of this essay reflected in Hamlet, a part we will consider in Section 8). Second, there is Cordelia herself, echoing Christ's own words at Luke 2:49: "O dear father,/It is thy business that I go about" (IV.iv.23-24). Third. there is her Gentleman's comment looking at the mad Lear running from her soldiers at Dover:

Cordelia also is the character whose devotion to truth, her refusal to flatter, starts Lear off on the path toward a truer and more humble understanding. I would suggest, however, that the way of Lear's redemption is not by way of the traditional Christ, who asked that people believe on him and be saved, and who suffered and died for them, but by way of the demiurge's repentance in Basilides' account--by self-knowledge, a humbling recognition of his faults. Certainly by the end, in the presence of Cordelia herself, come to save him from her sisters' wrath, he is all regret:

Yet despite all the suggestions that Cordelia is Lear's redeemer, it must be said that Lear is led to his awakening not just by Cordelia, but others as well, especially Kent, the Fool, Gloucester, and Edgar. They all carry certain role-modeling aspects for Lear's transformation. On the other hand, the negative characters, such as his elder daughters, also have a positive effect, by their shattering of his faith in them. He has an impersonal teacher as well, namely nature, which seems to mirror and intensify his moods, in the storm and the peaceful morning afterwards. His suffering, his own imitation of Christ, also plays its part, as we shall see later. Arrogance apparently needs suffering before it can listen to those who can teach it something important.

Edgar in particular has his own references comparing him to Christ, as we shall see in the section after next. I wish to emphasize that the correspondences are to a Gnostic version of Christ as opposed to the orthodox one. With the orthodox Christ, it would be hard to see how more than one character could symbolize Christ: that Christ, after all, is a unique individual whose unique sacrifice redeems all humanity (Roland Frye, 1963, 1961, makes this point, against those who see the play as a Christian allegory). In Gnosticism, as we shall see in section 5, what matters is the expression of a certain role, one modeling suffering, compassion, self-knowledge, and a certain way of being that is beyond suffering, which we shall examine at the end of this essay. Gnostics see Christ as the archetypal fulfillment of this role and way of being. Whether such a figure actually existed in history is then quite irrelevant: it is the image that matters.

The point about what or who brings about redemption, in the sense of self-knowledge, could be put more psychologically. What can change the narcissistic Lear, who demands unswerving and exclusive love from all? Such a narcissist is highly resistant to change, as long as he holds the power to get what he wants. He must fail in order to change, and begin to feel what Jung called a humbling of the ego. The ones who redeem him are precisely those who disappoint him and make him suffer: In Lear's case, it is first those whom he perceives as insulting him, Cordelia and Kent, but who also matter to him. Later his teachers are those who renege on their bargains, Goneril and Regan. These latter, unfortunately, have such an overwhelming feeling of having been wounded by him that they cannot show compassion for him; so he suffers in the storm and even more at the end of the play. Yet he has been just like those daughters himself, in his pitiless treatment of Cordelia and Kent and probably of the daughters themselves. As the Fool has said, in a witticism that is worth repeating:

Of her I take my leave forever, De leis pren comjat per jasse,This conclusion is not the typical troubadour one: they usually do not criticize themselves for loving, but only the other for not loving. Yet most of what Cardenal is saying fits Lear's experience, even though Lear’s setting is filial rather than romantic love. In storming out, away from both his older daughters, he "takes" his "leave forever." Like Cardenal, he compares them to serpents, the animals with venom, they who had seemed so sweet before (II.ii.350). They have certainly lacked "faith or fairness" in his eyes. From Cardenal’s list, guile and deceit are all that he has not charged them with. Finally, like Cardenal, Lear has commented on the blindness of love, in his remark about "blind Cupid," (IV.vi.134), and on how it has led him into danger. The song ends in a way that points to Lear's abuse of Cordelia and Kent as another part of his folly.

So that I may nevermore be hers; Que ja mais sieus non sia;

For not once did I find faith or fairness in her, Qu’an jorn no.i trobei lei ni fe,

But only guile and deceit. Mas engan e bauzia.

Ah! Sweetness, full of venom, Ai! Doussors plena de vere,

How love blinds the seeing man Qu’amors eissorba sel que ve

And leads him astray E l’osta de sa via,

When he loves that which ill behooves him, Quant ama so qu’ilh descove,

And that which he ought to love E so qu’amar deuria

Quits and distrusts! Gurp e mescre!

(Press 1971, 283-285)

Those last two lines also suggest that more may be at stake than romantic love, or even love between parent and child: The object of love is a "that which" (“so qu’,” short for “so que”) instead of a "she who." In such a case, "that which ill behooves him" could be a religion or an ideology as much as a person. Cardenal's medieval editors say that as a youth he had been a canon in the Catholic Church. One might wonder whether he might be blasting his excessive devotion and trust in that institution, given what it did later to the people and culture of his land. Perhaps when the Cathars were first attacked he distanced himself from them--that is, sought to "quit and distrust that which he ought to love," in the words of the song. In a world where suspicion of heresy could lead to imprisonment and dispossession of one's property at least, it was best not to be specific, and to let one's hearers interpret the moral themselves.

Such a perspective suggests another level in interpreting Lear's story. Lear's elder daughters, like most of those around him, had praised him as a god, in fact the god of Plato and orthodox Christianity, so perfect as to be beyond words and to whom other love is subordinate. Once humbled, Lear sees such praise as "no good divinity" (Iv.vi.99-100). On the level of divinity, this tale is not only about families, but about a social structure, patriarchal or not, that demands to be held in awe and lashes out when its evils and vulnerabilities are exposed.

But there is more here even than politics. It is a critique of any religion that sacrelizes that style of rule. What I see in Shakespeare here, as in Cardenal, is an echo of Gnosticism, specifically, its critique of the jealous God of the Hebrew Bible, whom the Gnostics called by various names: e.g. Yaldabaoth, Error, and demiurge. The word “demiurge,” meaning craftsman or artificer, came from Plato’s Timaeus, in which he imagined a lower level god doing the work of making the world, following patterns laid out by a higher god. For the Gnostics, such a craftsman was a highly imperfect one, a maker of counterfeits. The Cathars, the remnant of Gnosticism in the Middle Ages, carried on this tradition and denounced the God of the Catholic and Orthodox Churches as a “dieu etranh,” an alien god, as opposed to the “dieu juste,” the true god whom they worshiped (Nelli 1976, 38-39).

In Shakespeare's day, kings were seen as being to their lands what God was to his creation; kings ruled as the image of Providence. Lear's acts at the beginning of the play mimic those of the god of Genesis. First comes the void, Lear’s “nothing.” From this nothing came everything, the opposite of Lear’s maxim Next, the god divided light from dark and above from below; similarly, Lear divides his kingdom. In Lear's case, he is unintentionally creating disorder out of order, the reverse of Genesis (Calderwood 1987). Soon enough, we see the god of Genesis in Lear’s curses, first at Cordelia, then at Kent, and finally at his elder daughters. What is this but the same reaction to disobedience that Jehovah exhibits, cursing the beings that he has created in his image, first Eve, then Adam, then Cain, then all humanity except Noah and his family?

Later, in his "madness," Lear sees his earlier self as ungodly, “no good divinity.” Yet it is not that he saw the god of Genesis wrongly; rather, he sees the shortcomings of that god as embodied in himself. Now he is becoming Gnostic; for orthodox Christianity accepts even the god of Genesis as the one true god. This is where his, and Shakespeare's, insight lies, Gnostic in the very specific sense of the summaries contained in the polemical writings of Irenaeus and the ancient texts that correspond to them.

The Gnostics argued that the orthodox Judeo-Christian god--and by implication any institution modeling itself after that God--could not be the true god because of his faults--e.g. blatant favoritism, rages, and cruelty toward people who defied him (Williams 1996, Chapter 1). Gnostic texts called him arrogant, blind (in the sense of ignorant), and foolish. An example is from the Apocryphon (i.e. Secret Book) of John, one of a group of texts found in Egypt in 1945: